Wait For It! Attaining Success through Delayed Gratification

By Alana Lehrfield, LSW

“Don’t give up what you want most for what you want now.” –Richard G. Scott

Delayed gratification refers to the ability of an individual to resist doing something fun, pleasurable or rewarding now, in order to gain a more valuable reward in the future. For example, you could go to a movie the night before an exam to have a good time or you could practice delayed gratification and study for the exam, in order to meet the goal of doing well in school and graduating.

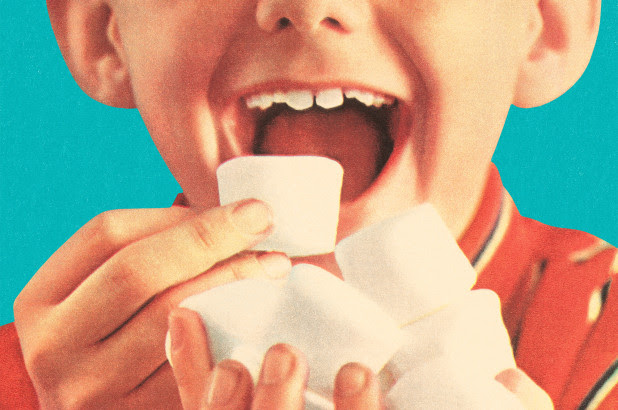

In the 1960’s and 70’s, a psychologist at Stanford University, Walter Mischel, researched the concept of delayed gratification in children. Called the Stanford Marshmallow Experiments, they have been considered the classic measure of self-control and delayed gratification in children for almost fifty years. In one experiment, researchers place a marshmallow in front of a four to six-year old, who has to decide whether to eat the marshmallow now or wait 15 minutes in order to receive a second. Only about 1/3 of the children were able to wait while the others squirmed and struggled, and eventually gave in to temptation. The studies followed the children over their lifetimes and found that the children who were able to wait for the second marshmallow had higher SAT scores, lower BMIs, less substance abuse and overall better life outcomes. These findings were thought to predict the child’s innate ability to delay gratification, a measure aligned with future success.

Interestingly, recent studies have shown that environmental factors influence the child’s ability to delay gratification as much as innate ability. Researchers at the University of Rochester’s Baby Lab created two distinct environments – unreliable and reliable. To set up the circumstances for the unreliable environment, the researchers promise to bring the children more crayons, and then fail to do so. Following this disappointment, the children didn’t wait for the second marshmallow because they didn’t trust that the researchers would actually bring it. However, the group of children whose researchers followed through on promises was able to wait up to four times longer for their treat. These findings lead us to recognize that human behavior is far more complex than we might imagine. They also illustrate the powerful impact our environment and support systems play on our ability to delay gratification and meet goals.

Delay Gratification:

Learning to delay gratification can support goal attainment in areas including, but not limited to: finances, health and fitness, education, career, and relationships. As adults, we recognize that there is not always a guarantee of a quick reward. For instance, we may not be able to fit into those jeans tomorrow, even if we go for a run today; instead, it can take months. We still may not be able to afford that vacation or dream home this year, even if we don’t buy that dress, car, or cup of coffee today. But we may be able to get better control of our finances, live within our means or build a nest egg for our future.

Most of us tend to be able to delay gratification more easily in certain areas of our lives and less so in others. For example, we may be able to set goals and accomplish them in school or work but overindulge at mealtimes. Or we may be extremely disciplined in our workout routine, but then blow our budget on new clothes. The areas in our lives where we repeatedly overindulge are called “hot spots,” a phrase coined by Professor Mischel of the Stanford study. And according to Mischel, we all have them.

Clearly, it can be extremely hard to be disciplined in our fast-paced culture where everything seems instantly available. Additionally, mental health challenges and living or working in unpredictable environments can thwart our best intentions and limit our ability to act in accordance with our values. Which can, in turn, create feelings of shame and inadequacy.

What can we do to harness the power of delayed gratification? We first need to visualize what we hope to achieve. If we imagine that we are like a garden, we need to tend to ourselves with a certain level of care by setting up the conditions for success. This includes the understanding and acceptance that it will take time and effort and an awareness of our own limitations and weaknesses or “hot spots.” We must nourish ourselves, weed out negativity, be patient and surround ourselves with relationships that support our growth and development. If the relationships in our lives are not providing us with the encouragement we need, seeking the support of a therapist may help.

Yet, beginning therapy is not easy. While it can be a fulfilling and worthwhile experience, it is not necessarily a quick fix. We have to show up bravely, week after week and we have to be willing to do the work. We have to have the courage to see ourselves for whom we truly are and accept ourselves, even if we are not presently where we want to be. Like the children in the second experiment, we also need a consistent, safe and trusting relationship in order to thrive. The therapist can function as that reliable constant in our lives, supporting us and helping us to identify our blind spots, heal past wounds, stay our path and reap the rewards of delayed gratification.